It’s January 30, 2025. A special date for this blog, as it marks the ten year anniversary of its launch. I’m a melancholic sort who often ponders the meaning of life and how short mine is, but as I reflect on the past decade I feel good about the work I’ve done here. Sure, for half of it I didn’t really make any posts, and some days my college years feel so very long ago. But it’s only been ten years since I was a sophomore! That’s not so much time, right? I’m still young… right?

Reading through my blog posts for the first time in a decade or so, I’m struck by how little my writing seems to have changed. Sure, I’ve got more life experience than the already-jaded college student who started this blog, but I feel my outlook on life and sarcastic writing style remains the same. I find myself not cringing at my younger self’s thoughts and opinions, a true luxury these days in a post-social media world. I think I might even have gotten along with past me, something else I imagine few can say. Sure, he could be an insensitive fool at times but that’s true of 2025 Ross as well, so… Can’t fault him too much for that.

But maybe ten years really is a long time. And maybe when something has lived that long, it’s time for a change. This blog has maintained its simple, Art Deco appearance for all of those years, and I feel like it deserves an update if I’m going to continue pouring creative effort into it. And thus, I have begun giving this site a fresh coat of paint, something that I hope will evolve it into an enhanced visual experience and submersion in the 20th century style and feel I want this blog to evoke. You may have also noticed the site has its own domain, no more .wordpress.com! For a year, anyway. Domains + hosting are expensive.

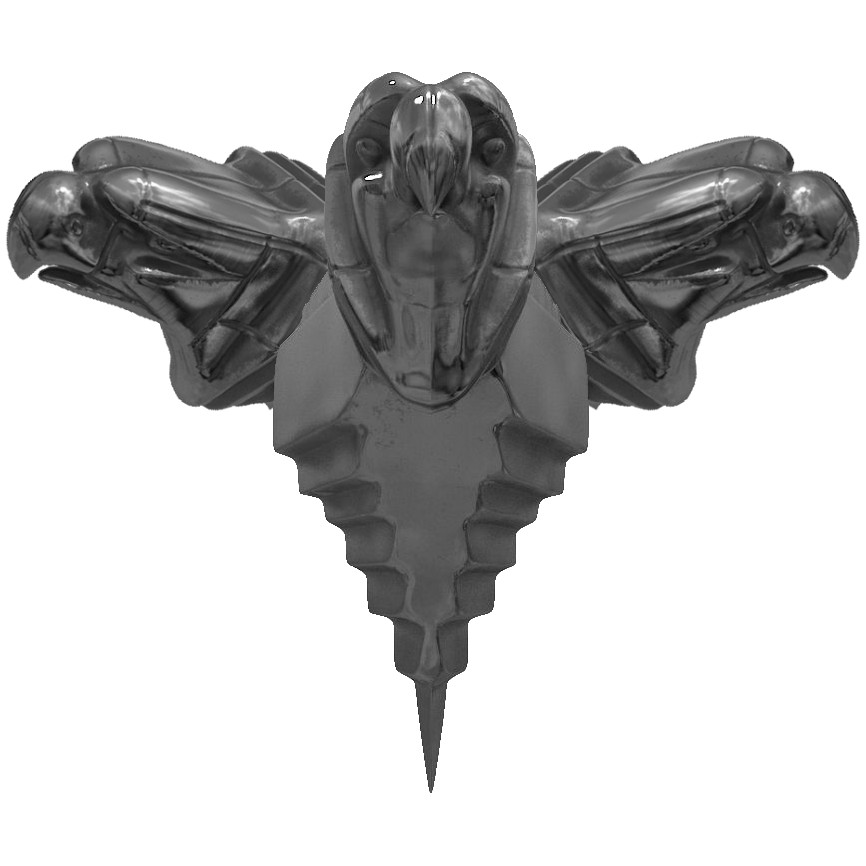

To honor that style I’ve loved for so long, let’s take a short journey through the architectural masterpiece that inspired my young, creative brain to the point where it has become a constant fixture in my mind as much as it is one on the New York City skyline: The Chrysler Building.

Now much has been said about this piece of art, so instead of writing a long history of the architect, the installation, and the broader details of what make it so brilliant (should be obvious), I’m just going to share some interesting facts and cool things I’ve gleaned over the years. The images are almost entirely from an amazing book I’d love a hardcover of – The Chrysler Building: Creating a New York Icon, Day by Day. Lots of cool shots of the building during its construction, which were almost lost to history when the author accidentally stumbled upon them as they were about to be destroyed.

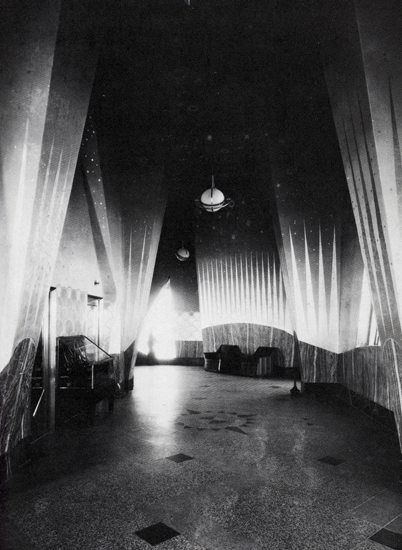

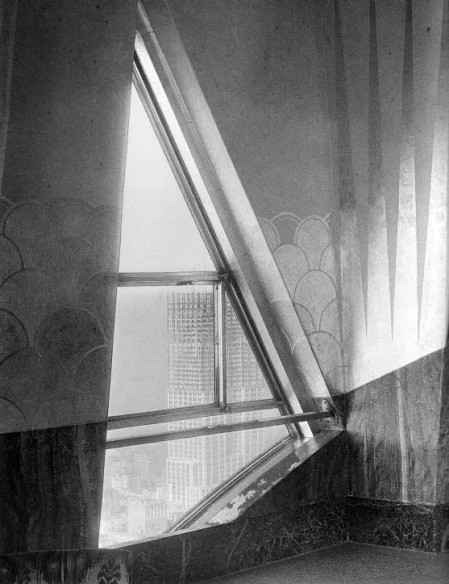

Firstly, I’ll share something that came to my knowledge recently. On the 71st floor of the Chrysler Building was a public observation deck which – though closed since 1945, was a marvel of modern design. A gallery called “The Celestial” had breathtaking, one-of-a-kind solar system adornments and a spacefaring vibe that would have absolutely made the feeling of looking across the blossoming Manhattan skyline something truly resplendent.

Gorgeous stuff – if only there were more photographs of this floor. Alas, it was closed in 15 years after opening and destroyed thereafter. Now the room is taken up by some soulless corporation instead of being open to the masses. If we can’t get it back for the people, I’d settle for it being my personal penthouse at the very least.

There was also a gentlemen’s club – more accurately a “millionaire cronies of Walter Chrysler club” that, in contrast to its Art Deco exterior, was decorated with a mishmash of a more traditional look & feel. Texaco, a tenant of the building, requested that a lunch club for executives be added to the building, and thus floors 66 – 68 became a strange amalgamation of medieval, Tudor, and modern styles so it could be more palatable to the traditional old dudes who would frequent it, much to the perturbation of the architect. The Cloud Club was not as short lived as the celestial – stuff for the rich elite always has a longer lease on life – but it did finally close in 1979 due to a lack of executive interest.

You can also view a cool gallery of club images here, as it looked later in its life.

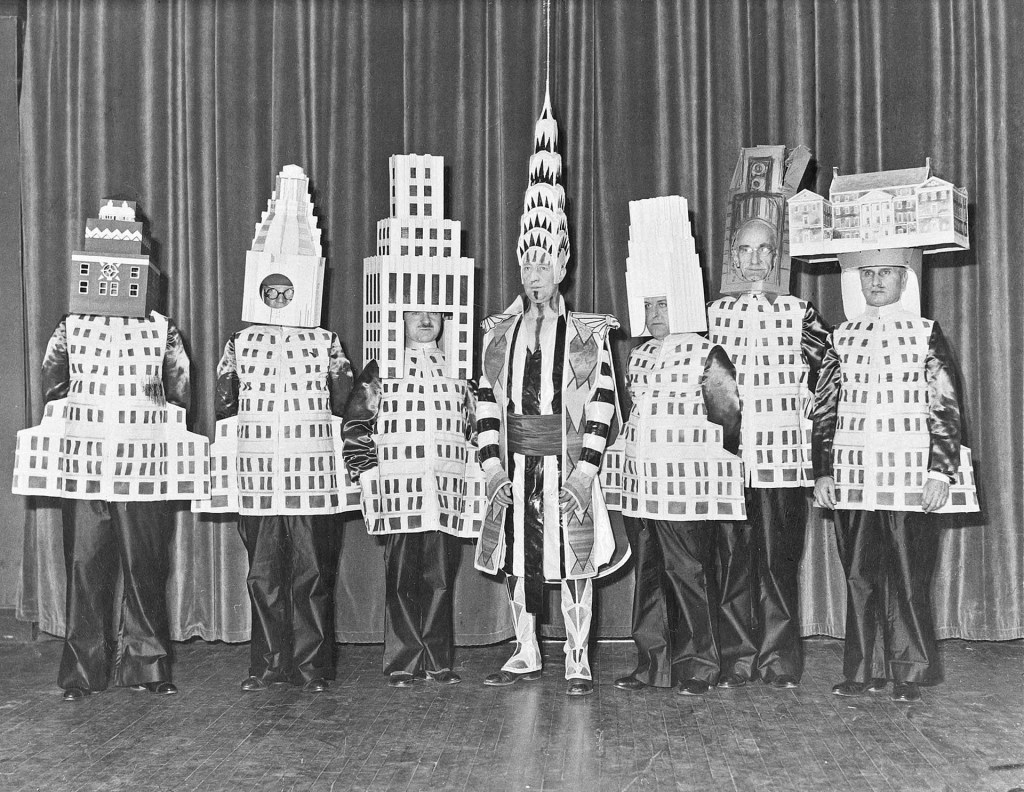

Something that might initially look silly but then become familiar, in our ongoing age of pointless extravagance and performative opulence, is this shot of the architects of several famous high-rises dressing up on stage as their own buildings. Their outfits and headwear wouldn’t be out of place on a runway in Milan in [present year], methinks.

Here you can also see a short video of the men milling about on stage, looking a mixture of amused and confused.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t share an incredible mini-documentary video with you. Narrated by John Malkovich, who is as big a fan of the building as I am, it is a very amusing and educational 10 minute romp. Whoever wrote it – I wouldn’t put it past the writer of some of it being Malkovich himself – has exactly the kind of sharp wit I like. Do yourself a favor and check it out – the video is screwy and repeats itself after the end, so you can close it around 10 minutes in. Enjoy!

Here’s to another decade of this blog. I have found it most entertaining to write, and I’ve learned quite a few things because of it, and we all know how much I love to learn. As I mention in my About pages, Cineri Gloria Sera Venit’s founding principle is to marry useful, interesting knowledge with a witty, entertaining presentation style. And, according to my three readers who all may or may not be related to me, I succeed in that endeavor. So why stop now?

I lied. One more after that. This is the kind of thing that makes me want to do Urban Exploration, which is the exploring of these kinds of dilapidated structures and abandoned places, often by flaunting the law. But hey, a small price to pay to see these beautiful places first hand. And this one can be visited legally 100 days out of the year! I’m in.

I lied. One more after that. This is the kind of thing that makes me want to do Urban Exploration, which is the exploring of these kinds of dilapidated structures and abandoned places, often by flaunting the law. But hey, a small price to pay to see these beautiful places first hand. And this one can be visited legally 100 days out of the year! I’m in.